The Brick Walls

In fall of 2016, local government agents and work crews descended on nearby Baochao Hutong, bricking up all the storefronts along the street. The authorities claimed to be restoring the alley to its “Ming Dynasty glory,” but in reality, the alley was a wreckage of messy brickwork and cement. Through the ‘tidying up’ of these streets, most of the storefronts in the hutongs were lost. However, despite the disruption, the neighborhood denizens did their best to continue daily operations. Local residents ducked into courtyards behind the freshly erected brick walls to patronize their regular vegetable stalls. The outraged web-sphere denounced the bricking as “classist” and “ruthless,” as most hutong businesses were run by lower-income migrants from other

provinces1.

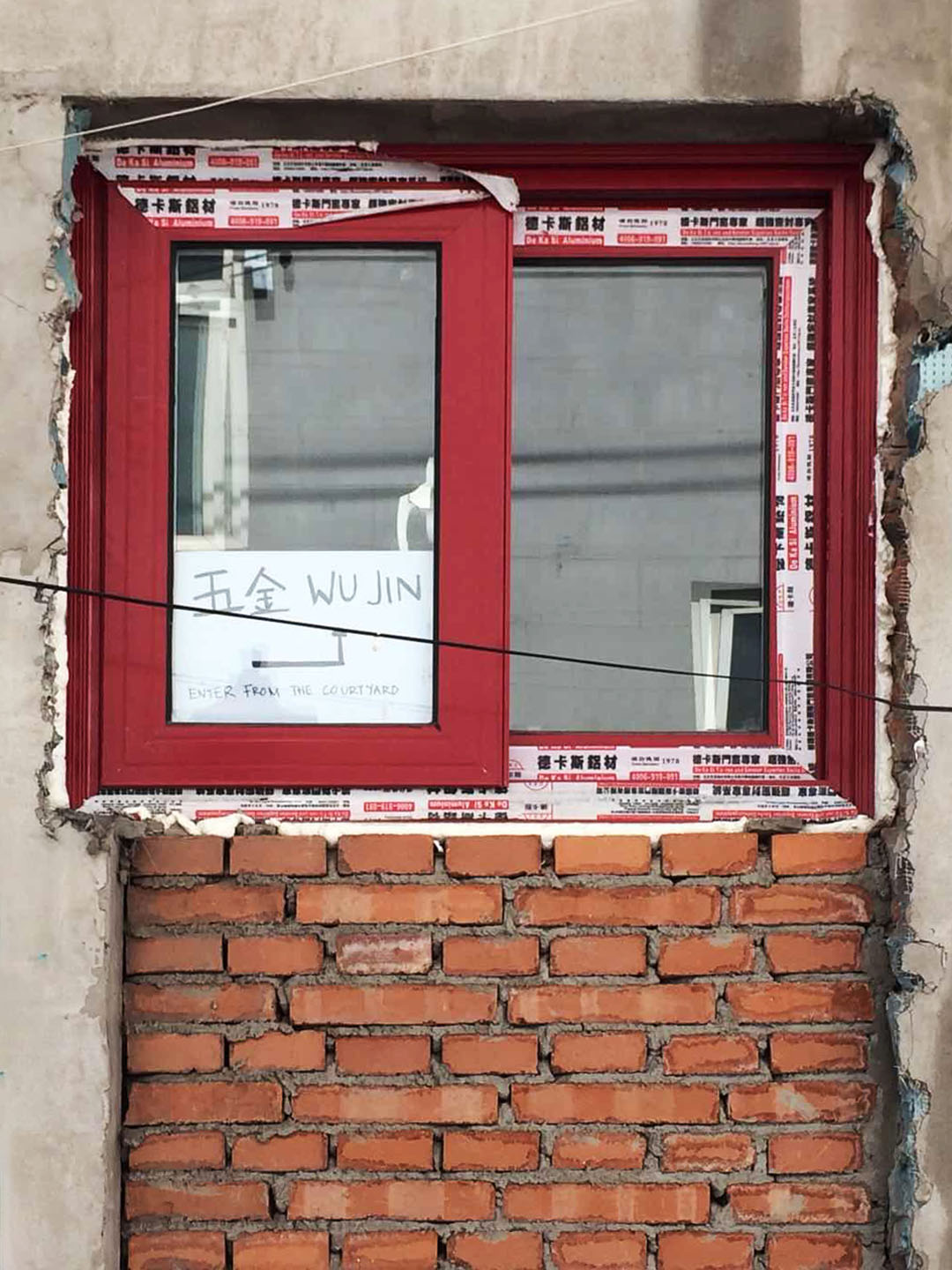

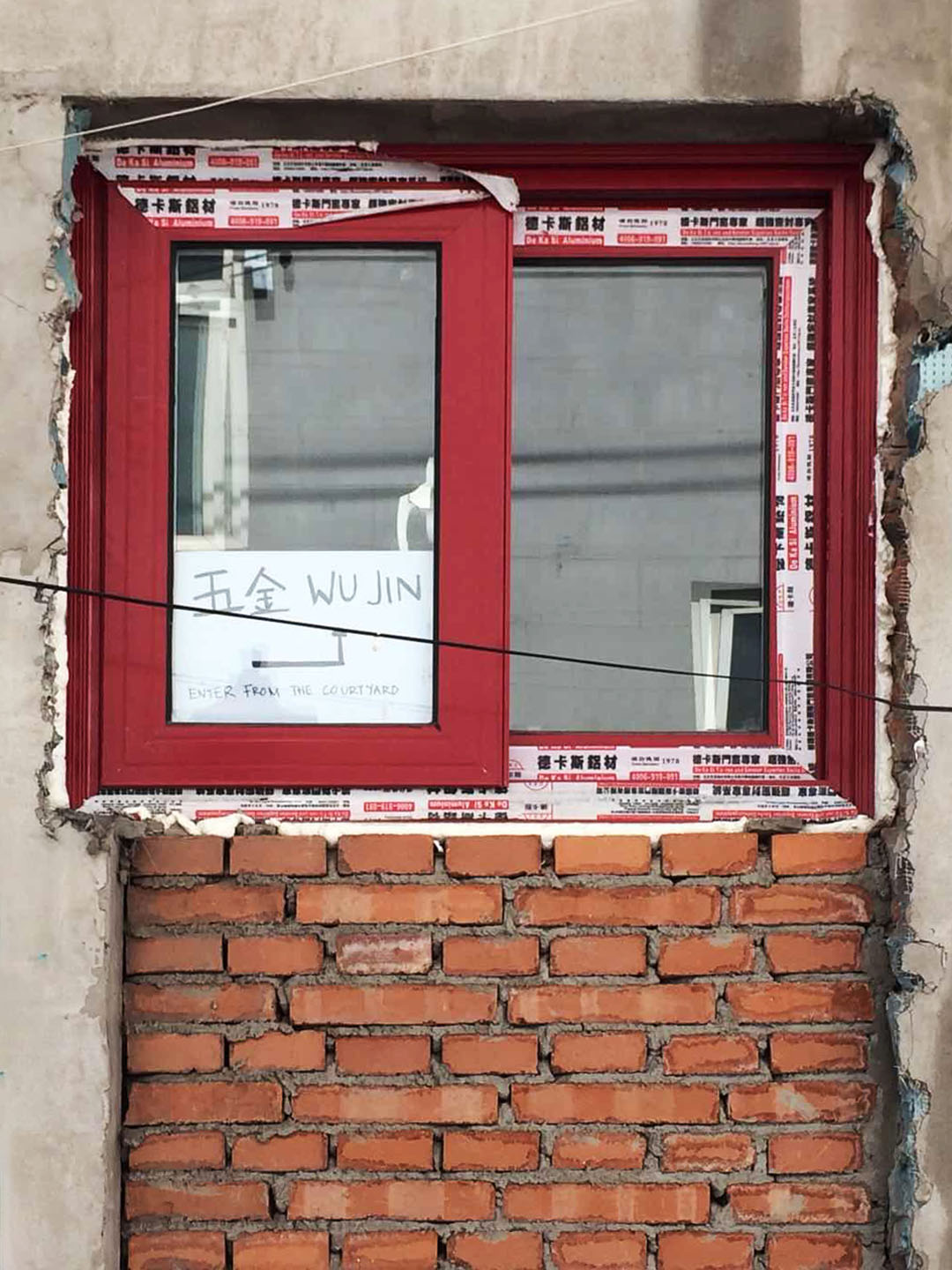

The local authorities ignored the public outcry, and work crews continued with the neighborhood ‘face lift.’ It was inevitable that Wu Jin would also meet this fate.

In May 2017, Fangjia Hutong, located just 200 meters south of Wu Jin, saw its lively bar and restaurant scene bricked up. After a few days of intense ‘retrofitting,’ most shop windows were either sealed off or reduced to a fraction of their previous size. Young partiers wandered the street in a daze, looking for the remains of their regular watering holes. A few bars placed ladders outside their doors-turned-windows for customers to either climb in or order drinks in take-away cups. The creativity of business owners and their patrons during this time was impressive and comical: resistance became a game. Unfortunately, in the months that followed, local government pressure increased, and eventually nearly all the hutong businesses closed up and left. Multiple coats of paint and detailed plasterwork erased the remaining ‘scars’ of shops that were once there, as if all that life never happened. For many small business owners, shopkeepers and merchants, this event was (and remains) a collective point of trauma. As the brick walls went up, the shop owners took cover and scattered in all directions—to other parts of the city, to their hometowns or into different business ventures. Many people never returned to the hutongs. Once the bricking ended, those who did return emerged shaken, resentful and saddled with economic as well as emotional loss.

On the morning of August 2, 2017, a stern-looking group of supervisors with hardhats and clipboards arrived to Jianchang Hutong. They pointed and shouted while pacing the street: “Change that door to a window! Close this opening up!” Crowbar wielding workers unceremoniously pried off Wu Jin’s glass facade and hauled it away. Moments later, the crews dropped a sloppy stream of bricks and mortar into the opening. It was painful to watch, but I felt an obligation to witness Wu Jin being transformed into a crypt. Staff members and regular customers with furrowed brows also came and went that afternoon. Many stood shaking their heads as they snapped photos of the destruction. Late in the day, as Wang Wei and I stood on the street, one particularly masochistic construction worker barked at us, asking where along the back wall he should cut a new entrance for the space. I sarcastically replied that his question was absurd, as the space was already trashed and unusable. The worker became indignant, and screamed that without more specific instructions, he would “not be responsible for messing it up.” Gripping a rotary saw in one hand, about to slash up a perfectly good wall, he stood in a choking cloud of dust. “Messing it up” is obviously a matter of perspective. As I opened my mouth for a more forceful reply, it came out as uncontrollable weeping. In my fury, I tried summoning Hannah Arendt, arguing that we are all ultimately responsible for our own actions, but all I could manage was incomprehensible blubbering. The worker stood there with a flat grin, intoxicated by this awkward scene and his fleeting moment of power. A few moments later, I stopped hyper-ventilating, pointed to a place along the wall to put a door, and he started sawing.